The Bright Start

In 1986, the Asian Games in Seoul captured the imagination of Indian sports fans. India finished with 37 medals and secured fifth place on the medal table. For many, those Games are remembered for the brilliance of PT Usha — the legendary Payyoli Express — who won four of India’s five gold medals in Asian record times.

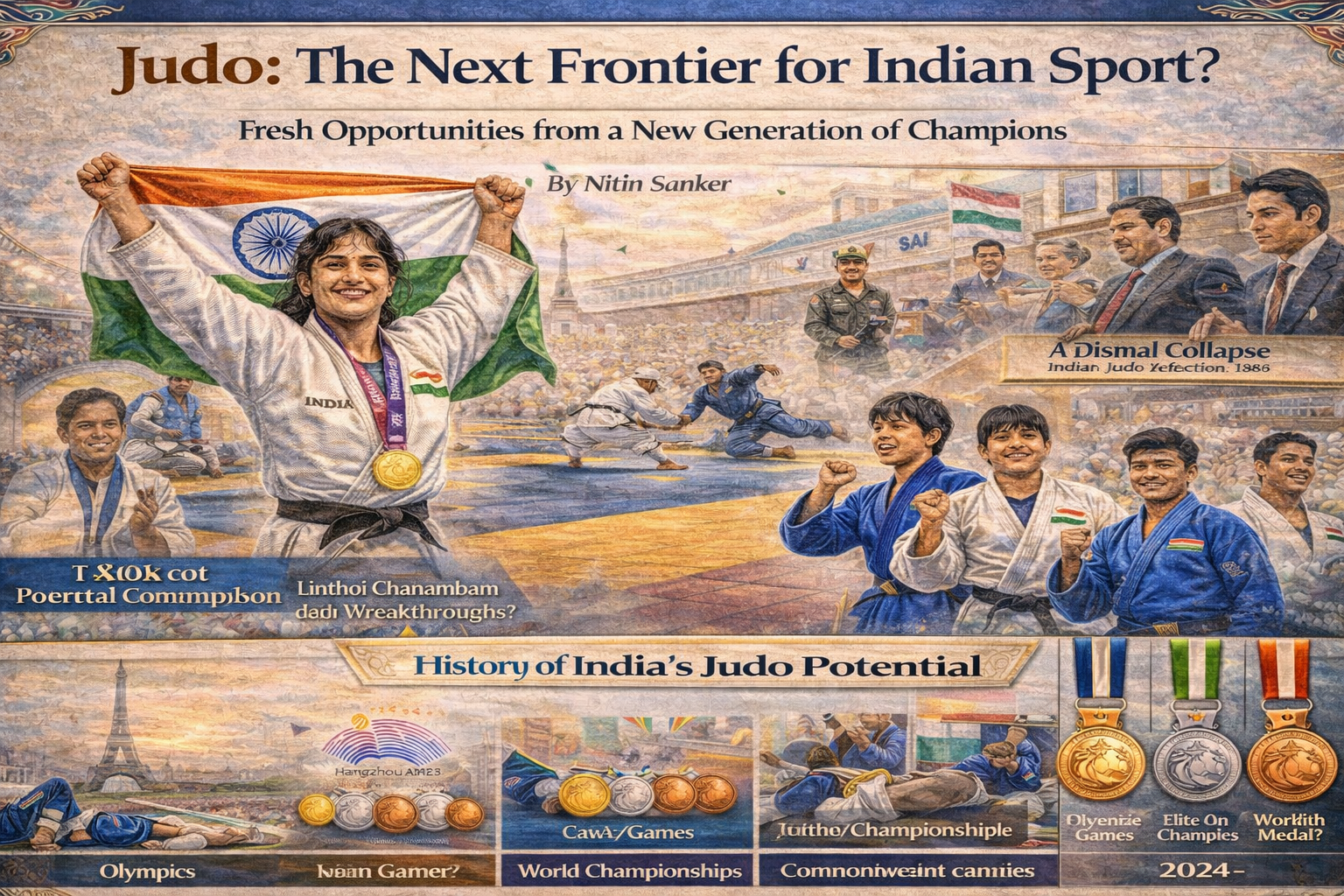

Yet beyond Usha’s heroics, the 1986 Games marked another milestone: the debut of judo as an Asian Games sport. India made a sensational entry. Led by Cawas Billimoria, the Indian judo team won four medals, instantly making judo India’s third-best sport at the Games — ahead of established disciplines such as shooting and wrestling.

For a brief moment, it seemed a powerful new contender had entered India’s sporting landscape.

The Dismal Fall

That early promise, however, proved deceptive. For any sport to flourish, three pillars are essential: a strong sports association, a charismatic star athlete, and sustained government investment in elite coaching and exposure. Indian judo lacked all three.

The federation became mired in administrative conflict and controversy. No breakout superstar emerged to inspire a generation. Government backing declined, and the sport slipped into disorder, eventually leading to the derecognition of the Judo Federation of India.

Since 1986, India has won only one additional Asian Games medal in judo — Poonam Chopra’s bronze in 1994. Olympic performances were equally sobering. India qualified a single judoka in 2012, 2020 and 2024 through continental quotas, but all were eliminated in their opening bouts.

The lack of support discouraged even exceptional talents. Tababi Devi, an Asian cadet champion and India’s first Youth Olympic silver medallist in judo (2018), left the sport at just 19, worn down by systemic challenges.

A New Source of Hope

Despite setbacks, Indian judo survived through dedicated grassroots coaches who kept the sport alive in regional pockets. Coaches in Manipur, Assam, Delhi and Punjab built strong local ecosystems that nurtured young talent.

Elite coaching is now emerging through institutions such as the SAI Centre of Excellence in Imphal, the Army Sports Institute, the Reliance Foundation and JSW Inspire. Administrative reforms have stabilized governance, and international exposure is increasing.

The impact of these changes is finally becoming visible.

Signs of a Breakthrough

For nearly 25 years, India’s top senior judokas hovered between world ranks 50 and 100. Today, the landscape is shifting. Young senior athletes are breaking into higher rankings, and India’s junior pipeline is arguably the strongest in its history.

This new generation includes Asian champions and world junior medal contenders, highlighted by Linthoi Chanambam — India’s first-ever cadet world champion in judo. Their success signals a structural transformation in the sport.

Why Judo Matters for India’s Olympic Ambitions

The Olympic medal table is shaped by sports offering multiple medal opportunities. While athletics and swimming dominate, a second tier of sports — including wrestling, boxing and gymnastics — provides significant medal potential.

Judo stands out as a cost-effective pathway. Equipment needs are minimal, infrastructure requirements are modest, and the sport is scalable within school and training environments. With a strong junior talent base already in place, judo offers India a realistic opportunity to expand its Olympic medal prospects.

The Road Ahead

A practical roadmap for Indian judo would include qualifying multiple athletes for the 2028 Olympics, winning Asian Games medals and contending strongly at future Commonwealth competitions.

Achieving this requires a world-class long-term coaching program, consistent international exposure and expanded elite athlete funding.

Final Outlook

If these elements align, Indian judo may finally convert decades of unrealized promise into sustained success.

For Indian sports fans, judo could become a new gateway to Olympic achievement — and words like ippon and waza-ari may soon enter mainstream sporting conversation.